Are Businesses Worldwide Suffering From a Trust Crisis?

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

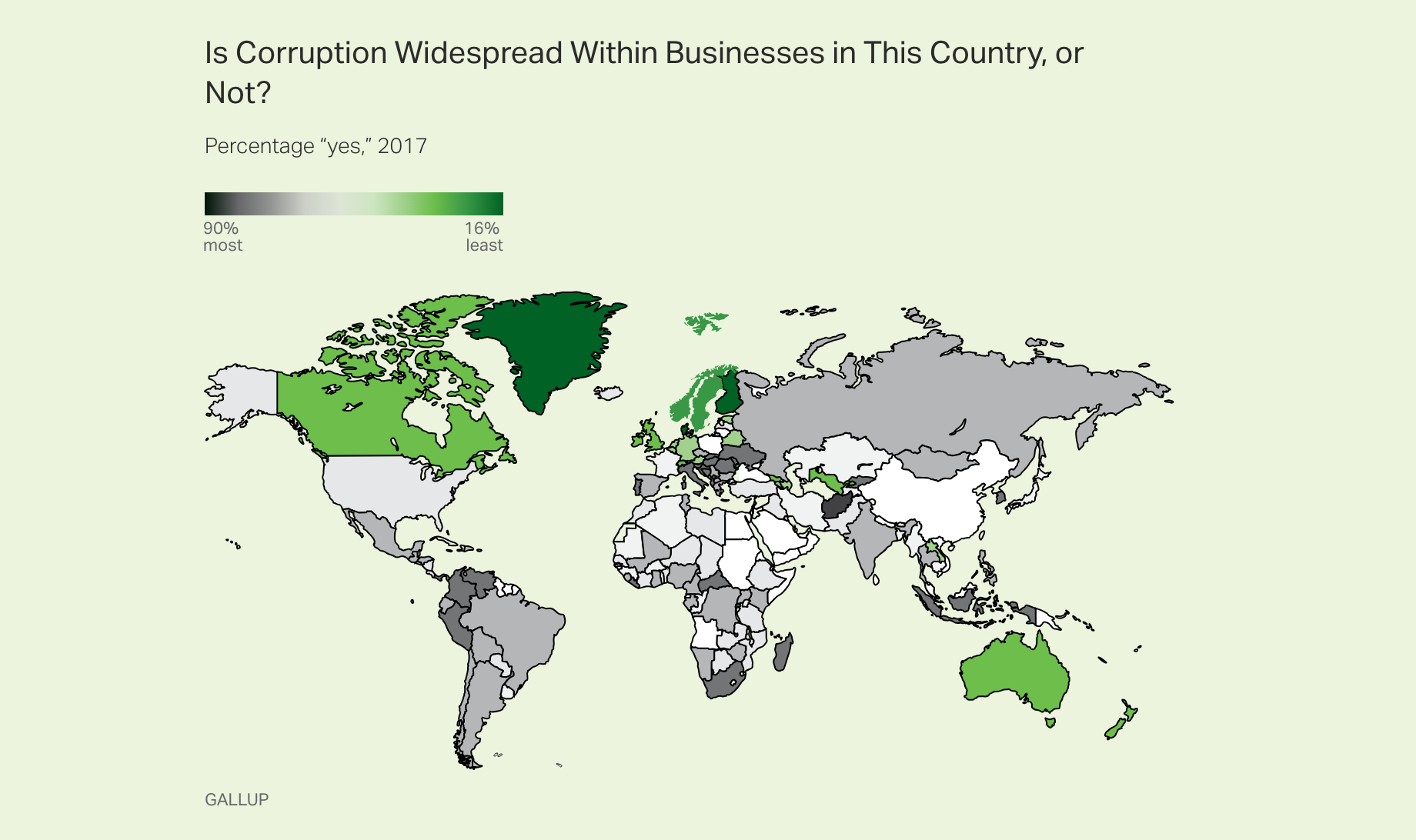

- Worldwide, two-thirds of adults say corruption is widespread in business

- There are three essential elements of a high-trust culture

- Many U.S. employees don't benefit from ethical compliance programs

This article is from The Real Future of Work: The Trust Issue.Download the full digital publication today.

"Trust is like the air we breathe -- when it's present, nobody really notices. When it's absent, everyone notices." -- Warren Buffett

The legendary American investor spoke the above quote following the 1991 Salomon Brothers bond-trading scandal, in which traders submitted false bids in an attempt to corner the U.S. Treasury bond market.

The scandal forced Buffett, a Salomon investor, to take over as interim chairman and root out unethical practices to help the firm avoid criminal prosecution. But Salomon Brothers was never the same; it eventually became part of Citigroup and most of its trading business was disbanded.

In the early 21st century, Buffett's observation about trust in business has only become more apropos.

The accounting scandals of 2001 to 2003 devastated corporate giants Enron and WorldCom among others, wiping out billions in shareholder value. And in 2008, widespread unethical lending practices triggered a global financial crisis from which it has taken a decade for many economies around the world to recover.

The widening impact of corporate misconduct in these cases highlights an irrefutable truth: In a globalized, highly interconnected world, trust is more important than ever to business success and sustainability over the long term. More than ever, integrity is the ultimate brand attribute.

Companies build trust on a daily basis in routine interactions with customers, consistently delivering on their promises or going to great lengths to rectify the situation when they cannot. They behave as if their customers' satisfaction and wellbeing are their most important considerations, leaving customers with a feeling of partnership rather than adversity.

That means establishing a culture in which all employees understand that their own self-interest and the interests of the organization are aligned with -- rather than unrelated to -- the interests of their customers.

That may sound self-evident, but many organizational cultures -- whether purposely or inadvertently -- encourage opportunistic behavior.

Poor moral leadership, performance incentives that lead employees to be single-mindedly hypercompetitive, lack of open and frequent discussion of ethical implications -- such attributes make it more likely that employees will view relationships with customers and even fellow employees with a zero-sum mentality.

In other words, they have a sense that their own success will come at the expense of others, which promotes ethical "blindness" and makes trusting relationships harder to sustain.

Worldwide, two-thirds of adults say corruption is widespread in business

Even for well-managed companies, establishing a reputation for integrity can be a challenge in the modern era, as employees, customers and investors in most countries start from a point of skepticism.

Residents of more economically developed regions are generally less likely to say corruption is widespread in business; nonetheless, 60% of adults in the U.S. responded this way in 2017, as did 52% in Western Europe overall.

Gallup's global research found that in 2017, 68% of adults worldwide believed corruption was widespread among businesses in their country. Worldwide, that figure has changed little over the past decade, though there has been significant movement in some individual countries, such as Germany.

Residents of more economically developed regions are generally less likely to say corruption is widespread in business; nonetheless, 60% of adults in the U.S. responded this way in 2017, as did 52% in Western Europe overall.

Within Western Europe, however, there is a strong north/south gradient; the vast majority of residents in several southern nations -- including Portugal, Spain and Italy -- say corruption is widespread in their country's businesses, versus less than one-third in the Nordic states.

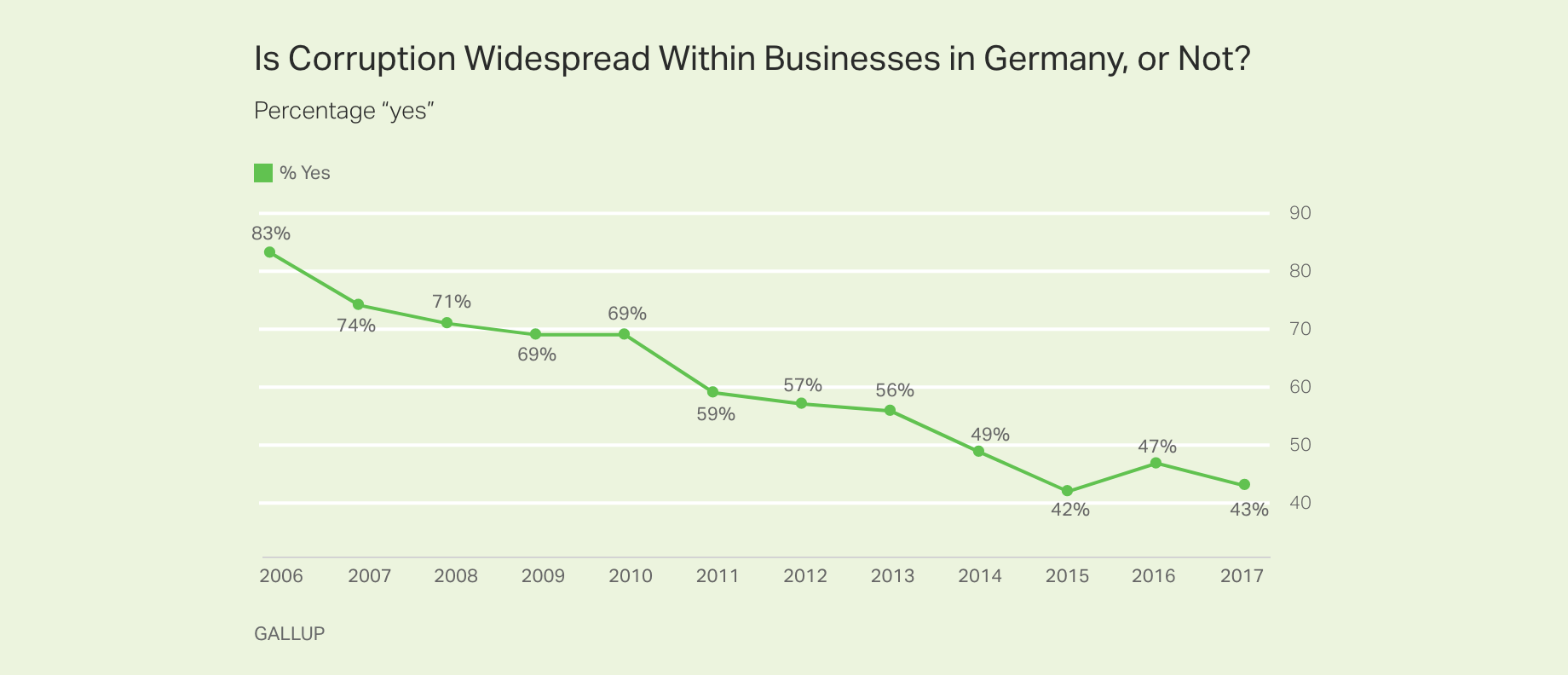

Germans have seen a clear decline in business corruption since 2006.

Germany offers a striking exception to the lack of change in perceived business corruption among G20 countries.

In 2006, 83% of Germans said corruption was widespread in the country's businesses; however, that figure dropped steadily over the ensuing decade to 43% in 2017.

Since the late 2000s, when high-profile corruption scandals rocked several large German companies, including the multinational conglomerate Siemens and the Volkswagen subsidiary MAN, German policymakers have increasingly targeted bribery and other forms of corporate corruption.

Among the most recent reforms is a 2015 measure that dramatically expanded anti-corruption legislation, including making it a criminal offense to offer, pay or take bribes in commercial practice.

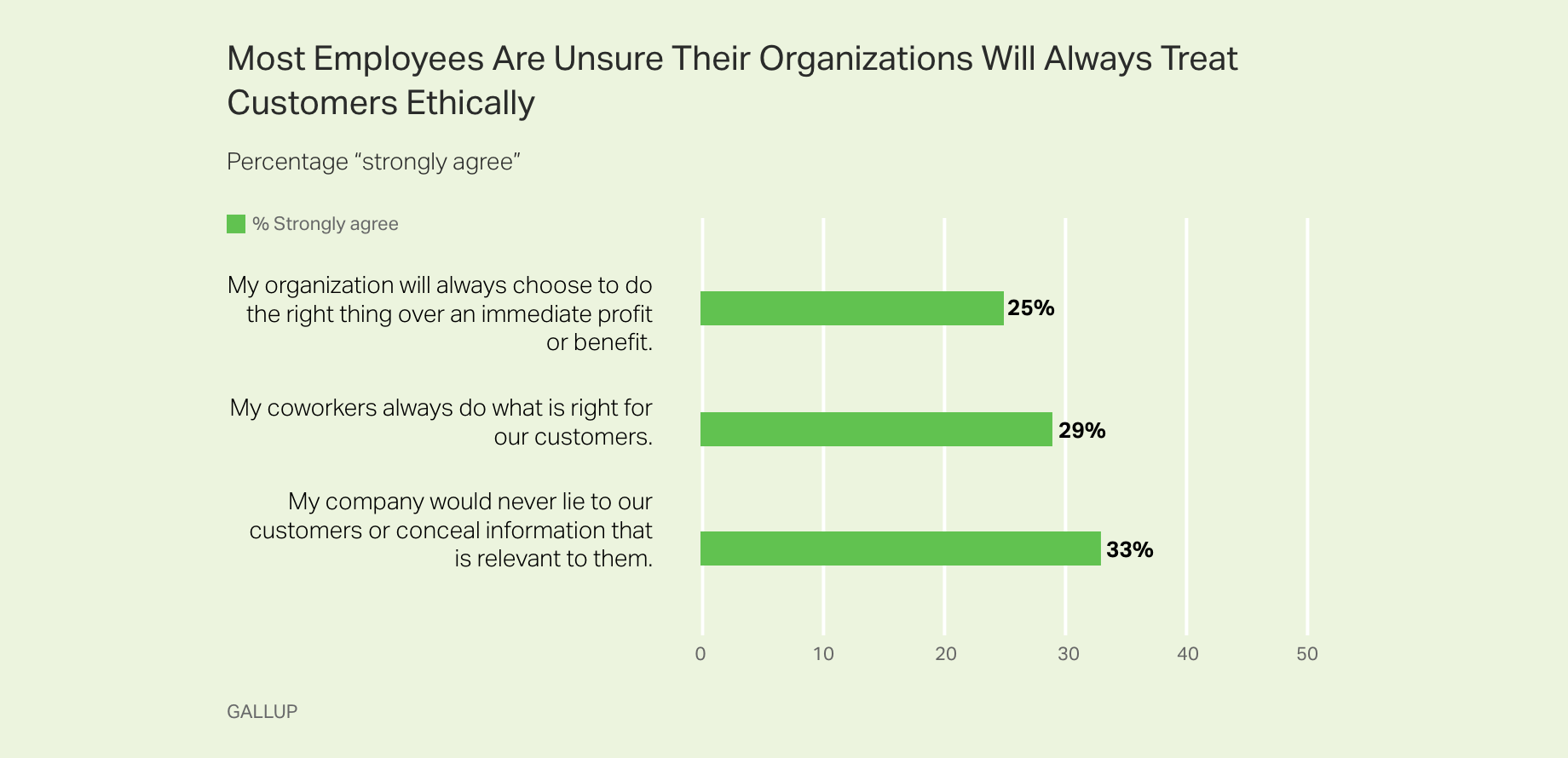

Most employees are unsure their organizations will always treat customers ethically.

In four European countries -- France, Germany, Spain and the U.K. -- Gallup asked employed adults how committed their employers are to doing the "right thing," especially with regard to customers.

In each case, no more than one-third agree unreservedly -- i.e., by selecting "5" on a 5-point agreement scale.

Most notably with regard to trust, just one-third of employees (33%) strongly agree that their company would never lie to its customers or conceal relevant information from them.

Ethical and business concerns have aligned in the global economy

In previous eras, trust was more often a product of ongoing relationships between individuals who did business together. People knew their bankers, merchants and employers personally and could assess the content of their character.

These days, business transactions tend to be less personal and more far-reaching than they were even a few decades ago.

Trust remains a vital form of business currency, but customers rely on different signals to convey a company's trustworthiness -- including, in many cases, a wealth of information about its ethical track record and the experiences of its customers and employees.

In fact, globalization is making adherence to commonly accepted ethical standards necessary not just for building trust with employees and customers, but for full-fledged participation in the worldwide economy.

Just as common technological protocols have made the rapid spread of mobile phones and internet around the world possible, common ethical standards provide a consistent set of rules that allow parties from different cultures and institutional environments to have confidence that they can do business together without being taken advantage of.

The success of global "sharing economy" platforms like Uber and Airbnb has been possible, in large part, because those businesses have developed transparent rating systems that help customers feel they can trust millions of new drivers and hospitality providers.

However, trust has also become a more important consideration within organizations.

Given the rapid pace of change in many industries, driven by digitization, globalization and emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, many employees wonder if their jobs are secure and need to feel that their managers are always open and honest with them.

The success of global "sharing economy" platforms like Uber and Airbnb has been possible, in large part, because those businesses have developed transparent rating systems that develop trust with customers.

Perceived trustworthiness has also become an important recruiting consideration.

Expectations for corporate responsibility have changed since the "greed is good" ethos of the 1980s.

Employees want to know their organizations operate in a socially responsible manner. Those who believe their company will always choose to do the right thing over making an immediate profit are more likely to say they would recommend it as a place to work and that they will stay there for another three years.

Gallup research has shown that millennial-age employees in particular want their careers to coincide with their personal values; they view their jobs as sources of meaning and purpose, rather than just a way to make a living.

Three essential elements of a high-trust culture

Businesses that sustain trusting relationships with employees and customers are distinguished by three central priorities, around which leaders build high-integrity organizational cultures.

Make strong customer value the ultimate business goal.

Organizations need an authentic, customer-centric purpose to guide their strategic focus and daily activities. Such a purpose, clearly and commonly articulated by leaders and managers, encodes ethical standards into the DNA of an organization.

If a company exists to improve the life of its customers, violating their trust or harming their communities through unethical behavior becomes not just a moral issue, but a strategic concern.

As an example, in restructuring their operations after suffering massive losses in the global financial crisis, many retail banks made restoring customer relationships their paramount leadership concern, with many articulating a renewed focus on customer-centricity supported by a set of clearly stated ethical standards and responsibilities.

By contrast, widespread concerns about Facebook's data-sharing policies and possible privacy violations have led to slower user and revenue growth and prompted a major ad campaign intended to regain users' trust.

Establish integrity as a primary organizational value.

High-trust organizations make integrity a core value that influences all HR processes, from performance incentives to hiring criteria.

Buffett once said he considers integrity a more essential hiring consideration than intelligence or energy:

"We look for three things when we hire people. We look for intelligence, we look for initiative or energy, and we look for integrity. And if they don't have the latter, the first two will kill you, because if you're going to get someone without integrity, you want them lazy and dumb." -- Warren Buffett

However, simply hiring principled employees isn't enough, particularly in an era when ethical implications aren't always obvious or clear-cut.

Recent research in organizational psychology points to "blind spots" that may lead people to behave unethically without being fully conscious of it.

The concept of bounded ethicality suggests employees often fail to recognize their own moral transgressions, either because the moral dimensions of their decisions aren't salient enough or because they conflict with other personal or organizational interests.

For example, in the accounting scandals of the early 2000s, major accounting firms were hired and paid by the companies they audited, motivating them to overlook inappropriate -- even fraudulent -- bookkeeping practices.

Employees need to see their colleagues acting under the assumption that integrity is an essential component of -- rather than an obstacle to -- their organization's success.

Such cultural norms ensure employees never feel that their own ethical behavior leaves them at a disadvantage. Conversations about ethics and trust and the consequences of business decisions should become part of a daily routine, especially as organizations embrace experimentation and constant innovation.

Ensure ethical issues are a major leadership focus.

For large organizations, trust is largely a product of leadership.

Business leaders help ensure employees are attuned to ethical issues by calling attention to them on a regular basis.

Unfortunately, many businesses pay lip service to compliance programs without conveying to employees the organization's commitment to building and maintaining customer trust through ethical practices.

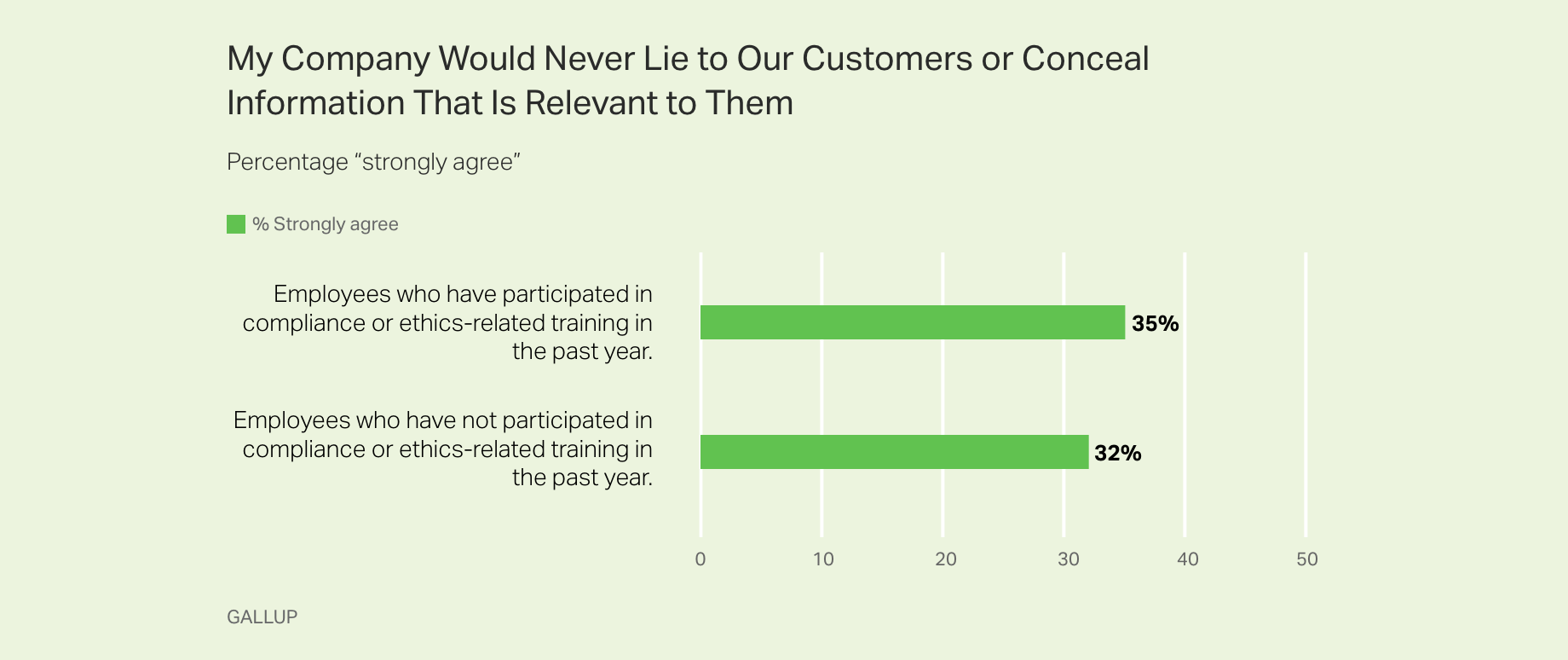

A recent study of U.S. employees similarly suggests that participation in compliance training alone is not very impactful.

About four in 10 European employees in Gallup's recent four-country study (39%) said they had participated in compliance training in the past year.

However, these employees were not significantly more likely than the others to strongly agree that their company would never lie to or conceal information from its customers (35% vs. 32%, respectively).

A recent study of U.S. employees similarly suggests that participation in compliance training alone is not very impactful.

Many U.S. employees fail to benefit from ethical compliance programs.

Gallup's recent study of U.S. employees suggests many of those who participate in ethics compliance programs do not find them particularly motivating or relevant to their jobs.

Out of more than 18,000 employees surveyed for the study, a little over half, 52%, said they had participated in an ethics training or education program sponsored by their organization. Half of those respondents said their program was web-based, while one-fourth said it was conducted in-person and the remainder received some combination of web-based and in-person training.

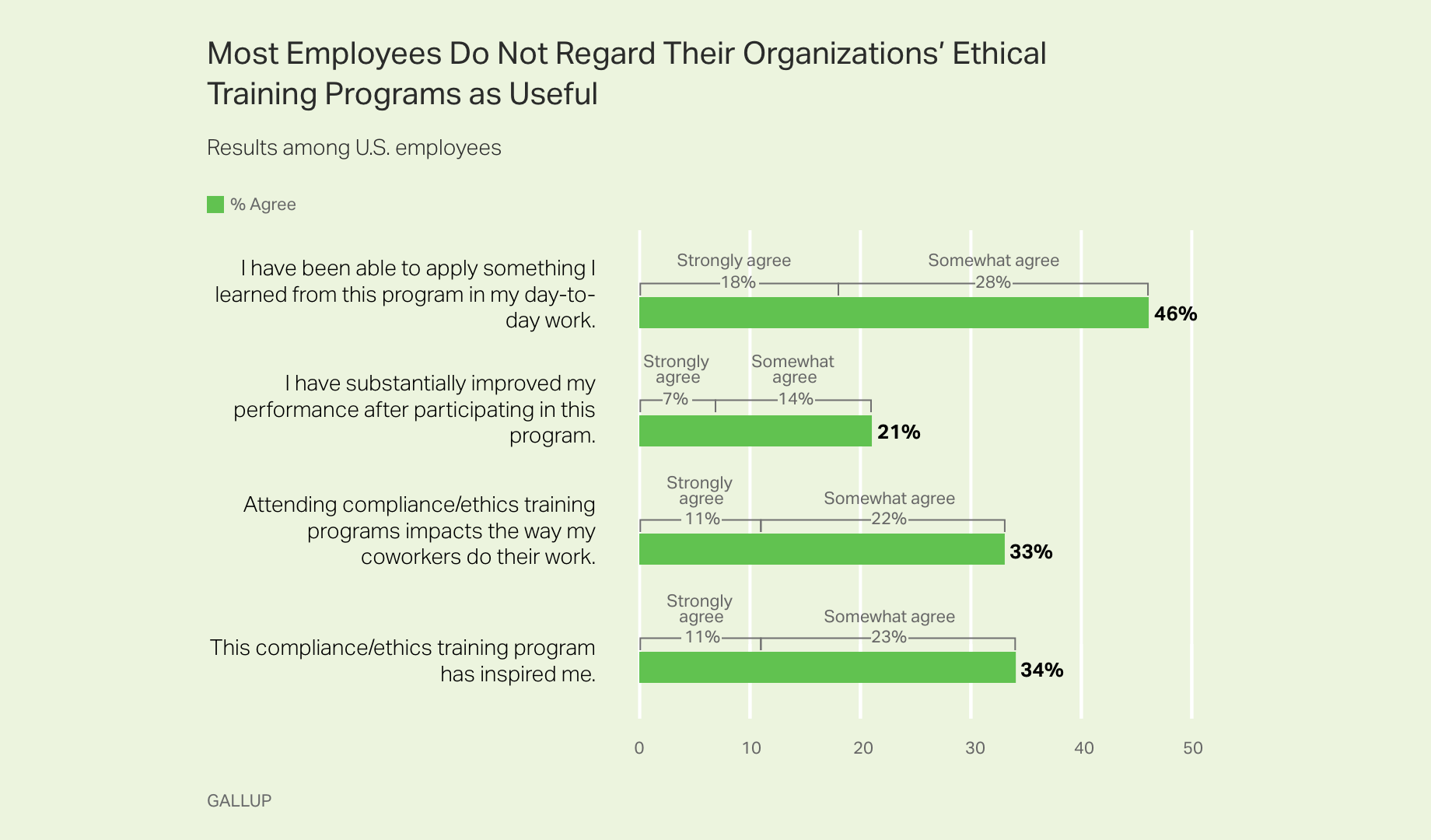

However, less than half of those who had participated in some form of ethics training strongly or somewhat agreed that they learned something from it that they have been able to apply in their day-to-day work (46%), while about one-fifth (21%) agreed that it has substantially improved their job performance.

One-third (33%) agreed that participation in ethics training impacts the way their coworkers do their work.

About one-third (34%) also said their ethics training had inspired them, suggesting a lack of effort on the part of many organizations to imbue such programs with meaning beyond legal or regulatory implications.

Employees who have more routine opportunities to grapple with ethical concerns, however, do tend to view their employers differently.

Across the four European countries studied, 32% of employees said their teams regularly discuss ethical issues relevant to their jobs; one-fourth (26%) say their teams do not regularly discuss ethical issues.

Among those employees who say their companies discuss ethical issues regularly, almost half (48%) strongly agree that their company would never deceive its customers.

Such findings point to the role of managers in maintaining a day-to-day focus on ethical vigilance. This is because managers are on the front lines ensuring that performance targets and incentive systems do not lead employees to (consciously or unconsciously) make unethical decisions, that employees are fully aware of ethical issues relevant to their work and that their team members feel free to express any ethical concerns.

Overall, 39% of employees in the four European countries studied strongly agree that if they raised a concern about ethics or integrity, their employer would do what is right -- but that figure rises to 61% among those who are extremely satisfied with their immediate managers.

Ultimately, strong ethical leadership is a big part of what gives employees and customers the confidence to invest in long-term relationships with organizations.

Strong ethical leadership is a big part of what gives employees and customers the confidence to invest in long-term relationships with organizations.

The one-fourth of employees in the four-country study who strongly agreed that their company will always do the right thing over an immediate profit are considerably more likely than the rest to strongly agree that they are confident in its financial future -- 56% vs. 32%, respectively.

Most understand that their organizations' choice to make integrity a cultural imperative implies a preference for sustainable success over short-term opportunism.

Additional Steps

- This article is from The Real Future of Work: The Trust Issue. Download the full digital publication today.

No comments:

Post a Comment